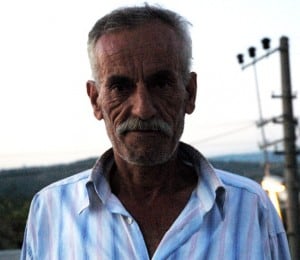

Sezai was my security man; he guarded the building projects at night, tidied up at the end of the day, burnt anything that would burn and spent the hours of darkness watching over the materials on site.

When we first met him he was mad as a box of frogs, sinewy lean and tough and with what, back in the day, I used to call a lack of impulse control. Most of the village was terrified of him, not just because of the gleam of madness in his eyes but because his reputation as a man likely to whip out a knife to settle an argument was well known. This is the kind of man who makes a good security guard.

He slept on site and would arrive at sunset ever night, strolling laconically up from the tea shop, cigarette in hand, several knives no doubt secreted about his person, keen to get on with some guard duty and hopeful that someone would turn up so he could arise out of the darkness like a vengeful Bedouin out of the shadow of a sand dune and cheerfully brandish his knife at them.

Only once did he get to enact his raki fuelled dreams of springing into action like a righteous lion of justice. When we first moved here and were working on what was the become The Muses House the lightest fingered man in the village thought there might be easy pickings on the site after dark. Very drunk one night, and by the light of a full moon, he attempted to scale the wall intent on making off with any insignificant trifles that might be lying around. He reckoned without Sezai who, ever alert to the opportunity to frighten the shit out of someone, was lurking in the mulberry bush on the other side of the wall.

The moonlight must had flashed dramatically on Sezai’s long and deadly sharp knife as he leapt into action, springing forward with a guttural cry, his teeth bared in a fearsome snarl. There was a short sudden cry, a thump, and then the swift patter of flip flops retreating through the lanes.

“He is stupid” said Sezai when he told me about it a few days later “çok aptal, he came back the next night and tried again.” He spat on the floor in disgust as someone so foolish as to think that a second attempt would succeed. “I made sure he won’t come back again!” he added with satisfaction and smirked, a gruesome sight made all the worse by the leprous yellow of his ruined teeth.

Every time I’ve seen the little thief around the village since he won’t look me in the eye, he ducks his head when he sees me and slinks to the side of the lane and he has changed tea shops, a sure sign of guilt, moving to one as far away from Sezai as possible. Which is wise, because the forests behind the village are huge and trackless, and bodies might disappear into them; the evidence mulched into nothing by burning sun and fearsome rain, gnawed away to nodules of bone by wild boar and kicked into the drifts of pine needles by passing hunters. Sezai could dispose of whole regiments of thieves in there.

As the years went by Sezai did get saner, he wanted a new wife and so he had to clean his act up and he stopped drinking so much raki, switching instead to village wine, which makes you drunk but not insane and gradually the madness faded from his eyes.

Somehow he secured a wife, or an old one returned, we’re not entirely sure, but these days Sezai’s life is a lot more comfortable. His house down by the main street has been refurbished, no doubt with the money he salted away working for me, and his beloved rose garden is a bee humming hymn to flowers, riotous and colourful and tended with love and care. I see a pretty middle aged woman in there bustling about, cooking and cleaning and chattering away as Sezai leans on the garden wall, slowly sharpening one of his assortment of knives and giving the evil eye to any passer by because old habits die hard.

Sezai works down in the village bakery these days, and he is in charge of setting and maintaining the fires for the mighty brick ovens. It’s the perfect job for Sezai because if he can’t stab something he’ll happily set it on fire and his urge to create mayhem is satisfied by feeding the greedy fires of the ovens with anything he can lay his hands on.

“You are good?” I asked him when I met him on his way to the tea shop the other afternoon for a quick glass of cay before a little light incendiary work.

He nodded.

“No drink?” I teased.

He shrugged, the ever so meaningful loose limbed, ear high shrug of a village man, “A wife is like the Jandarma in your bed” he confided to me, and then he grinned, a sly winking grin because he knew I’d seen the little bottle of raki tucked in his pocket.

“Deli!” I admonished him, “Size cok deli, you are mad!”

He laughed, and strolled on, relaxed gait, hands in pockets, ever so slightly menacing, confident in his madness. Telling someone they are insane is something of a compliment here.

One of the many aspects of Turkey I really love is the social acceptance of the weird and the wonderful. It says a great deal about social cohesion. It’s just as well as I’m sure without it we’d be marched out of town!

Sounds like a real character and the best security guard ever! x

when the village was fighting to stop the quarry and cement works in Kocadere, J and I were seen as the ringleaders by the developers who got very nasty, making serious threats. Every night we had a ring of fully armed villagers securing our house and lives – it was a scary time. The villagers wanted nothing more that the outsiders to turn up like lambs to their own slaughter. When they did show up they were hunted across the fields and orchards with shotguns blasting – they left, abandoned their project and never returned. Turks make great friends and dangerous enemies.

This is one of the best posts I’ve read in a while. Anywhere. Sezai sounds like a real character, to be sure, but your writing brings him to life.

Thanks for a great read.

Awh thanks, he is just like that, he is a big character. Karen

After reading this deliciously well-written and engaging post, I am homesick for our own A. – who helps us mind the place on Bozcaada for the long months we are away. Although I am not sure about a knife, the burning and raki-wife navigation are so familiar!

I concur in the admiring comments to the Sezai story. A real character, lovingly described by you, Karen. I remember him from your earlier blog entries. Villages in Turkey do have a compassionate way of accepting those inhabitants that are slightly off kilter, even while often making fun of them. It’s a sign of the intimacy they feel towards them. Crazy or not, if they decide you’re one of them and that you belong, they’ll defend you to the death.